- OR the magical distinction between YA and adult literature

- OR why Mia Thermopolis is not the same as Lee Fiora

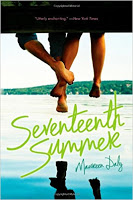

amongst publishing professionals. We point to Maureen Daly’s 1942 novel

SEVENTEENTH SUMMER, the National Library Association’s coining of the phrase “young

adult” in the 1960s, and the 1970s heyday of Judy Blume and Robert Cormier . We

marvel at Harry Potter and Twilight, and we look uncertainly into the mid-twenty-first

century, as “chick lit” and “new adult” came and went faster than the kale fad.

Now, we ask ourselves, what’s next for YA – and what is (was) it anyway?

What, for example, makes Curtis Sittenfeld’s PREP or SPECIAL

What, for example, makes Curtis Sittenfeld’s PREP or SPECIALTOPICS IN CALAMITY PHYSICS by Marisha Pessle adult books, while prep school

turns by E. Lockhart (THE DISREPUTABLE HISTORY OF FRANKIE LANDAU-BANKS) or

Daisy Whitney (THE MOCKINGBIRDS) are intuitively placed on the young adult

shelf?

novel with a high school-aged protagonist a work of young adult literature? The theme of most replies to this question is

that YOUNG ADULT novels feature not only teen protagonists but cathartic – dare

I say hopeful – endings. That, in the end, the protagonist emerges not merely more

or less triumphant over mortality or evil or agnostic despair but, also with a

sense that things will take a turn for the better. So, in simple sum: optimism

equals young adult. Can that be? I think there’s more.

In terms of narrative structure, Martel’s and Sittenfeld’s protagonists

tell their tales looking back ruefully, with sober comprehension that they are

not, in fact any better now than they were when their stories unfolded and that

the world is a place that demands less-than. In adult fiction, if you’re a

princess you’re Diana, not Meghan Markle.

Sometimes it takes more courage not to let yourself see.

Sometimes knowledge is damaging – not enlightenment but enleadenment. – Blue van

Meer, SPECIAL TOPICS IN CALAMITY PHYSICS by Marisha Pessl

In the end, there was always your regular life,

and no one could deal with it but you. ― Lee Fiora, PREP by Curtis Sittendfeld

Meanwhile, Cabot’s and Whitney’s teen protagonists reach

their stories’ ends “un-enleadened.”

Yes, I am a freak. But you know what? Someday, I just might

grow out of that. But you, you will never stop being a jerk. — Mia Thermopolis, THE PRINCESS DIARIES MOVIE

based on the novel by Meg Cabot

It is not mere optimism that Mia reveals, but a greater sense

It is not mere optimism that Mia reveals, but a greater senseof evolutionary identity – the possibility of transcendence, of transformation.

Despite their youth, the teen protagonists of adult novels emerge from their

travails “sadder but wiser” as the cliché goes. Meanwhile, Daisy Whitney’s Alex

– not unlike J. K. Rowling’s wizard hero Harry Potter – takes on a leadership

role in the group that initially saved her life and becomes, on a

bigger-than-self scale, a fighter against evil. And Cabot’s Mia Thermopolis finds

out both that she really is royalty and

that she can be noble on her own terms.

defines a novel’s genre so much as the sense that who we are is not all that we

can or will be. That, perhaps, the world can be saved. And that hope is not lost

EXPRESSLY BECAUSE of our own innate potential. Or, to quote a red-head:

Anything is possible

if you’ve got enough nerve. – Ginny Weasley, HARRY POTTER series by J.K. Rowling